Új kutatási eredmények (2013 január) alapjaiban változtatták meg az SM-ről alkotott képet. A legmodernebb MRI leletekkel bizonyított, hogy a szürkeállomány sérülése az SM legkorábbi szakaszában megtörténik és a megfigyelt vas kiválás, valamint atrópia (agyi oxigénhiányos állapot) mértéke összefügg a gyulladás mértékével:

... A number of clinical observations as well as recent neuropathologic and neuroimaging studies have clearly demonstrated extensive involvement of the thalamus, basal ganglia, and neocortex in patients with MS. Modern MRI techniques permit visualization of GM lesions and measurement of atrophy. These contemporary methods have fundamentally altered our understanding of the pathophysiologic nature of MS. Evidence confirms the contention that GM injury can be detected in the earliest phases of MS, and that iron deposition and atrophy of deep gray nuclei are closely related to the magnitude of inflammation. ... forrás: (pubmed link)

Hogy ez miért fontos? Erről már 2011 májusában közöltem egy posztot, lássuk újra:

Az SM diagnosztikája jelenleg főként MR készülékkel történik, a fehérállomány gócait térképezik fel. Ez azért van, mert a fehérállomány demielinizációját vagyunk jelenleg képesek megjeleníteni MR készülékkel. De talán nem látjuk a teljes képet...

Csak mostanában vagyunk képesek a szürkeállományt is vizsgálni MR-rel. De mi van ha eddig nem a megfelelő vizsgálatokat végeztük? Mi van ha az SM-nek nem a fehérállományban bekövetkezett mielinvesztés az oka, hanem a szürkeállományban bekövetkezett atrópia?

(A szürkeállomány az agy egy része, mely az agy oxigénszükségletének 94% -át használja el normál esetben. A teljes agy 40%-a a szürkeállomány és 60% a fehérállomány.)

Amikor az EAE modellt dr. Rivers létrehozta az 1930-as években,

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2212888/ akkor az emberi fehérállomány sérüléseit, gócait akarta egerekben modellezni: mivel csak azt ismerte az akkori tudásával. Ezt úgy érte el, hogy idegen antigéneket injekciózott az egerek agyába, ahol létrejött egy immun reakció, ami hasonlított az emberben - az emberi fehérállományban! - látottakra. Az összes mai SM gyógyszer úgy született, hogy az egerek EAE betegségét gyógyítják vele. És emiatt az emberekben nem is működnek olyan hatékonysággal… hogy miért? Mert az EAE és ADEM korántsem egyenlőek az emberi SM betegséggel… lássuk miért.

Az EAE jellemzően a fehérállomány betegsége, és nincsen benne nagyfokú szürkeállomány atrópia.

Az EAE egy valódi autoimmun betegség egerekben. Elfogadták, hogy ez az SM betegség egérmodellje. Ez a hibás feltevés oda vezetett, hogy az emberi SM betegséget is autoimmun betegségnek tartják, és ennek alapján készítik a gyógyszereket és végzik a kutatásokat. Ez a tévedés tragikus hatású.

http://www.mednat.org/vaccini/sclerosi.pdf

A progresszív SM betegségben nem figyelhetők meg fehérállomány gócok, nincsen mielin pusztulás, nincsen gyulladás… a betegség mégis romlik tovább. Miért? Hogy lehet hogy az SM "jól ismert" jelei nem igazak a progresszív formára, ennek ellenére a beteg állapota rohamosan romlik? Mi változik, amikor az SM progresszív lesz? Mi van ha SEMMI nem változik, és mi egészen eddig rossz tüneteket figyeltünk meg, mint például a fehérállomány gócok megjelenése? Hogyan lehet hogy egyes emberek 20 ilyen góccal az agyukban vígan bicikliznek, míg mások 2 góccal nem tudnak járni?

- "Eleinte az SM betegséget elsődlegesen fehérállomány központúnak gondoltuk - mondja Bianca Weinstock-Guttman neurológus - de mára már tudjuk, hogy a szürkeállomány sokkal inkább érintett mint a fehér."

http://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/178458.php

A következő tanulmányban a legmodernebb MR technológiával vizsgálták az SM betegek szürkeállományát. Arról szól, hogy a korai alacsony felbontású MR készülékekkel csak a fehérállományt lehetett vizsgálni, de ma már a modern készülékekkel láthatóak a "strukturális és funkcionális agyi károsodások" is.

A bizonyítékok sorra gyűlnek, hogy a kortikális demielinizáció és atrópia fontos faktor a progressziv SMben.

http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/msj.20247/abstract

A következő tanulmányban a fehér és a szürkeállomány gócokat vizsgálták és arra jutottak, hogy szürkeállomány demielinizácója a fehérállomány demielinizációjától FÜGGETLENÜL zajlik le. Ez azért fontos, mert sok neurológus azt állítja, hogy először van a fehér, aminek következénye a szürkeállomány sérülés. Nem, ezek függetlenek:

http://archneur.ama-assn.org/cgi/reprint/64/1/76.pdf

A következő tanulmány arról szól, hogyan vizsgálható manapság a szürkeállomány sérülése SM-ben:

"A szürkeállomány gócok az SM legkorábbi fázisában is kimutathatóak és ezen gócok mennyisége és nagysága ÖSSZEFÜGG az SM beteg tüneteivel. (szerk. megj: nem úgy mint a fehérállománynál, ahol ezek nem függenek össze!) Ezek a szürkeállomány gócok egyben nagyon jó előrejelzői is az SM betegség jövőbeli várható állapotának.

http://www.mendeley.com/research/cortical-lesions-in-multiple-sclerosis/

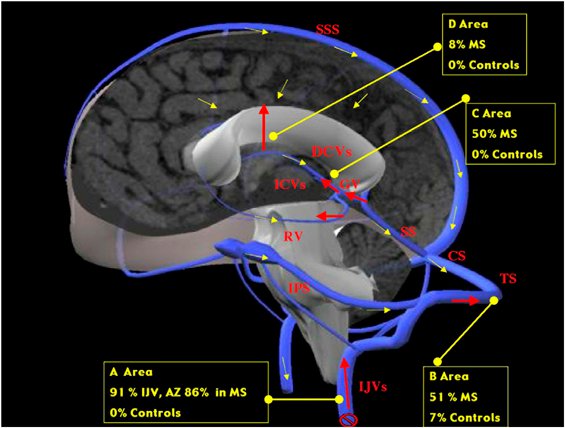

A következő képen az látható, hogy a Zamboni által talált vénás reflux hogyan érinti a szürkeállományt is:

Új eredmény: a következő videón a Hubbart Foundation által koordinált CCSVI tanulmányokból láthatjuk a legújabbak eredményeit. Dr. Giedrius Buracas ismerteti, hogy az általuk végzett fMRI BOLD vizsgálatok alapján a CCSVI érinti a kortikális területek oxigénellátottságát, sőt megmutatja, hogy a vénatágítás javít a szürkeállomány működésén! konkrétan a 10. perctől látható ez:

A fenti prezentáció első része itt, a Hubbard Foundation összes videója itt érhető el.

Lassan fel kellene ismerni, hogy a közel 80 éves (!) egérmodell a továbbiakban már nem pontos, nem fedi le a jelenlegi tudásunkat az SMről. Tovább kellene lépni végre, fel kellene ébredni a 170 éves álomból és a tudományos tényeket kellene figyelembe venni, nem pedig ósdi egérmodelleket védelmezni. Az érvágás is kiment már a divatból itt az ideje, hogy az EAE is megtalálja a helyét: a nagy tévedések panoptikumában.

A gyógyszergyáraknak persze érdekük, hogy az EAE modellt védjék, hiszen erre tették a pénzüket, erre fejlesztik a gyógyszereket, és sok-sok év, évtized, amíg egy gyógyszer megtérül. De ez legyen az ő bajuk. Az internet segítségével immár hozzáférhetőek a legújabb kutatási eredmények és mi páciensek olvassuk ezeket és addig harcolunk amíg a mi érdekeink képviselete fontosabb lesz a profitnál.

A fordítás Joan Beal összzfoglaló cikke alapján készült.